THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS: PART THREE

THE RULE OF THE CONGREGATION (MESSIANIC RULE)

THE RULE OF THE CONGREGATION (MESSIANIC RULE)

There is a Scroll that was found in Cave One which was originally included in a larger scroll called the Community Rule or Manual of Discipline which we have already discussed. It appears, however, to be a complete work in itself. It sets down rules for behavior in the "congregation of Israel" in the "last days," as they prepare for a war. Therefore, the contents of this Scroll are related to what we see in the War Scroll.

In this Scroll, the priests, or "sons of Zadok," are described as the highest leaders in the community but there also is reference to a messiah or messiah’s who will lead Israel in war against their enemies.

The rules of life that are set down are meant for everyone who has "kept the covenant," men, women, and children. After a brief introduction, rules are given for males from youth to full adulthood. They are to be taught beginning when they are children, and at the age of twenty become full members of the community. At this time they are also old enough to fight in the holy army. As they grow older they are expected to increase in responsibility and be given higher and higher positions of leadership, depending upon their strength. Special duties are given to the men of the tribe of Levi (the Levites) and they are to be under the authority of the sons of Aaron (the priests).

As in the biblical book of Leviticus, those who have some kind of impurity, or physical defect, are not to take part in the community council, nor are they to have any leadership role. The text ends with a description of the "community council" and instructions for the drinking of bread and wine together. The first to enter "the assembly" is the chief priest and other priests, then the "Messiah of Israel" together with the chiefs of the clans of Israel, the wise and the learned men. When they drink the new wine, the first to take the bread and wine should be the high priest, and then the Messiah of Israel. This is how each meal should be eaten.

It is important to realize that the figure of messiah as seen in the Scrolls does not have the significance that it does in the NT documents. In the Scrolls, the Messiah of Israel is seen more as a political and military leader whose status is lower than that of the high priest. This should plainly tell us that the Qumran sect is not in any way related to the Christian community of the first century as we know that Jesus is seen as superseding the Aaronic priesthood.

THE ZEALOTS:

We earlier discussed a group of radical Jews who had one goal in mind and that was to drive the Romans out of Judea and restore Judea to being independently ruled by the priesthood. It was the Zealots who precipitated the war with Rome that began in A.D 66 and ended with the defeat of the last stronghold of the Zealot’s at Masada in A.D. 73. Because of the detailed manner in which methods of war against the enemies of the Qumran community are laid out in the War Scroll, it is believed by some scholars that the Qumran community was not associated with the Essenes but with the Zealots. We saw earlier that there is a great deal of similarity between the beliefs and practices of the Essenes and the Qumran Sect. This is why most scholars who have studied the Dead Sea Scrolls believe these two groups are the same. The term Zealot was a name applied to those who were actively planning to overthrow Rome. A reading of the War Scroll clearly shows the Qumran sect believed war was imminent and they would be the victors.

While it is evident the Zealots were a radical group of activists bent on bringing about an open rebellion against Rome, it is also evident the Qumran community believed the time had a arrived for the appearance of the Messiah or Messiah’s who would lead them in war against the Romans and save them from Roman oppression. In all likelihood the Essenes and the Qumran sect were one and the same and shared in the aspirations of the Zealots who are not seen as being as religiously legalistic as the Essenes and Qumran sect but more bent on being aggressively involved in bringing down Rome. As covered earlier, the Zealots also believed that the time was at hand for the Messiah to deliver them and restore the Kingdom of Israel. This is why they had the audacity to fight a war which by themselves they had no chance of winning.

ADDITIONAL DOCUMENTS:

At the time the Qumran community was thriving, the Biblical canon of Scripture had not yet been totally fixed. The Torah, much of the prophetic literature and the Psalms were already considered canonized Scripture. Additional documents, however, were still being considered for inclusion in the canon. As covered in the series on the reliability of the Biblical Scriptures, there were many documents being used within the Jewish community which did not get included in the final group of approved documents that became known as the Hebrew canon of Scripture. Remember, canon is a group of documents authorized and approved by some designated person or group of persons who have been appointed to establish such authorized and approved group of documents.

As can be seen from the discoveries at Qumran, this group was using a number of documents that did not become part of the Protestant canon of Scripture but did become part of the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox and Ethiopian Church canons. For example, eleven copies of the book of Enoch were found at Qumran. All these copies were in Aramaic. Enoch, as translated into the Ethiopic language, is included in the Ethiopian Christian canon to this very day. Eighteen copies of the book of Jubilees, written in Hebrew, were found at Qumran. The book of Jubilees recites the book of Genesis and Exodus, chapter’s one through fourteen, and is presented as a revelation by angels to Moses on Mount Sinai. The text of Jubilees frames the Biblical narrative into a series of jubilee years (50 year) periods which is based on the jubilee-year system found in Leviticus 25. Jubilees’ is found in the Ethiopic canon of Scripture.

Fragments of the apocryphal books of Tobit and Ben Sira were found at Qumran and were written in Hebrew. Tobit tells the story of a righteous Israelite of the tribe of Naphtali named Tobit living in Nineveh after the deportation of the northern tribes of Israel to Assyria in 721 BC. Ben Sira is a small book containing a double list of alphabetically arranged proverbs. Twenty-two are in Aramaic and twenty-two are in Hebrew. This book was apparently written around 180 B.C. by a Jewish sage named Ben Sira. Though this book is believed to be apocryphal by the Protestant world, it appears to have been held in high esteem by the Jewish rabbis as it is quoted in the Talmud which first came to be centuries after the Qumran community disappeared. The book of Tobit is part of the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox canon of Scripture as is Ben Sira which is found under the name Ecclesiasticus.

A document written in Aramaic called the Genesis Apocryphon was found in cave 1 and recounts events recorded in Genesis from the time of Lamech, the father of Noah to the time of Abraham. This document provides an account of Abram speaking in the first person and telling how representatives of the King of Egypt gave a glowing account of the beauty of his wife Sarai.

How beautiful is her face! How fine are the hairs of her head! How lovely are her eyes! How desirable her nose and all the radiance of her countenance. How fair are her breasts and how beautiful all her whiteness! How pleasing are her arms and how perfect her hands, and how desirable all the appearance of ho hands! How fair are her palms and how long and slender are her fingers! How comely are her feet, how perfect ho thighs! No virgin or bride led into the marriage chamber is more beautiful than she; she is fairer than all other women Truly, her beauty is greater than theirs Yet together with all this grace she possesses abundant wisdom, so that whatever she does is perfect."

When the king heard the words of Harkenosh and his two companions, for all three spoke as with one voice, he desired her greatly and sent out at once to take her. And seeing her, he was amazed by all her beauty and took her to be his wife, but me he sought to kill. Sarai said to the king, "He is my brother," and so I, Abram, was spared because of her and was not slain.

THE PSALMS:

In cave 11 was found a well preserved Psalms scroll containing most of the Psalms found in our present canon of the Hebrew Scriptures. What is interesting is that many of the Psalms in this Scroll appear in a different order from what we see in our present canon of OT Scripture. Of greater interest is that there are five additional psalms at the end of this Scroll which are not included in our present canon of psalms. However, these additional psalms were known to exist in a Syriac translation of the Hebrew Scriptures before the discoveries at Qumran. Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic used by some early Christians and is still used today by the Syrian Orthodox Church. In the present day Syriac translation of the Scriptures called the Peshitta, you will find these additional psalms added at the end of Psalm 150. Psalm 150 is the last of the Psalms in the generally accepted canon of the Hebrew Scriptures.

It should be noted that Aramaic was largely the language of first century Judea and is the language apparently spoken by Jesus. This has been determined by linguistic analysis of the kind or words Jesus spoke as recorded in the NT. Much of the two Talmud’s were written in Aramaic.

THE COPPER SCROLL (3Q15)

The Copper Scroll is probably the most intriguing and baffling of the Scrolls found at Qumran. Reading it is akin to reading something out of an Indiana Jones movie script. This Scroll describes vast amounts of buried treasure. It begins with the following paragraph:

"In the fortress which is in the Vale of Achor, forty cubits under the steps entering to the east: a money chest and its contents, of a weight of seventeen talents."

The Copper Scroll was discovered by archaeologists in 1952 in Cave 3. The text of this document had been incised on thin sheets of copper which were then joined together. At the time it was found, the document was rolled into two separate scrolls of heavily oxidized copper which was far too brittle to unroll. For five years scholars discussed ways of opening the scroll. Finally it was decided to cut the scroll into sections using a small saw. Working very carefully, they cut the scroll into 23 strips with each one curved into a half-cylinder. Before it was cut, one scholar thought he saw words for silver and gold and suggested that the scroll was a list of buried treasure. As it turned out, that is exactly what the Scroll was about. It’s about buried treasure.

The treasure described in the Copper Scroll consists of vast quantities of gold and silver, as well as many coins and vessels. It is difficult to assess the value of what is described since we are not sure what the weights in the scroll are actually equivalent to. But, it was estimated in 1960 that the total would top $1,000,000 in U.S. currency.

With this great amount of treasure described as being somewhere, many have searched for it but have come up empty. Or if someone has found it they aren’t telling anyone. The problem is that it is almost impossible to determine the location of this supposed treasure. While the narrative on the Scroll is in Hebrew, it also contains a number of Greek terms. Many of the geographical locations described have not been identified. The Scroll reads like a treasure map, giving very specific twists and turns one must take in finding the treasure. Since 2000 years have passed since this scroll was written, many of these twists and turns no longer exist. The vocabulary of the Scroll is very germane to the landscape of the time it was written. Obviously this landscape has changed over 2000 years.

Some have suggested the treasure never actually existed and the Copper Scroll is simply a work of fiction. Would someone go through the trouble of incising print on thin sheets of copper if all they were doing was writing fiction? Some believe the scrolls refer to Temple treasure, hidden for safekeeping before the destruction of the Temple in A.D. 70. Still others believe the treasures described in the Copper Scroll may belong to the Bar Kokhba rebels who were involved in the second Jewish revolt against Rome in A.D. 132-135. The bottom line is we just don’t know much about what this scroll is telling us.

THE TEMPLE SCROLL:

The Temple Scroll (11QT) is a virtual reworking of the laws of the Torah. Much of it is a reflection of what is written in Deuteronomy although Exodus and Leviticus are also well represented. A major feature of the Temple Scroll is that it quotes God in the first person whereas in Deuteronomy, Moses is seen as speaking in the first person and God is seen as speaking in the third person. For example, in Deuteronomy Moses often refers to the place of worship as the place where God will choose to set His name. In the Temple Scroll, God is seen as saying, “the place upon which I choose to set my name.” In Numbers 30:2, we see, “If a man makes a vow to the LORD.” In the Temple Scroll we see, “If a man makes a vow to me.”

God is portrayed as talking directly to the people with the scribe only recording what God is saying. Some scholars believe this indicates the Qumran scribes may have believed God was directly revealing to them the contents of the Temple Scroll. The Temple Scroll is the longest single text fund at Qumran. It appears to be an attempt to take all the laws and regulations found in the Torah and place them into a single narrative by combining what is said on any particular issue into a single presentation. For example, the Torah prohibits the eating of blood. In Deuteronomy the instruction is to spill the blood on the ground. In Leviticus the instruction is to spill the blood on the ground and cover it with dirt. In the Temple Scroll, Deuteronomy is quoted with the additional instruction from Leviticus included in the same narrative. The Temple Scroll is a virtual consolidation of instruction pertaining to a particular issue. This approach is found throughout the Temple Scroll.

BIBLICAL MANUSCRIPTS FOUND AT QUMRAN:

As we covered in the first presentation in this series, about one-fourth of the 930 documents found at Qumran are manuscripts and fragments of manuscripts of the OT Scriptures. These copies of OT Scripture are approximately 1,000 years older than the copies of the OT we had prior to the Dead Sea Scroll find. Prior to the Dead Sea Scroll discovery our next oldest copies of the OT Scriptures dated to the early middle ages.

The most represented books of the Hebrew Scriptures found at Qumran are the Psalms, Deuteronomy and Isaiah. There were 34 copies of parts of the Psalms, 27 copies of parts of Deuteronomy and 24 copies of parts of Isaiah. It is interesting that these three books are the most cited by writers of the NT documents. In addition, there were copies of 20 parts of Genesis, 13 parts of Exodus, 9 parts of Leviticus and 8 parts of Daniel found at Qumran. Also found were copies of parts of “the book of Twelve,” which is a compilation of the twelve Minor Prophets which were considered a single book in Jewish tradition.

Some parts of copies of the Torah found at Qumran are written in Paleo-Hebrew script which is the style of Hebrew script used in ancient Israel before the destruction of the first temple. After the destruction of Solomon’s temple and sometime during the fifth century B.C., Hebrew scribes began to change the style of the script and most of the Scriptural documents found at Qumran are in this changed style of script. An analogy would be the change from Old English script to our modern way of writing English.

The manuscripts found at Qumran initially went through paleographic analysis which is the study of handwriting. The handwriting found in the scrolls was compared to the hand writing of various periods of historical time and it was found that the handwriting found in the scrolls dated the scrolls to the third, second and first centuries B.C. Radio carbon dating has confirmed these dates for the writing of the scrolls.

TRANSMISSION OF SCRIPTURAL INFORMATION:

How was the information contained in the Scriptures transmitted through the historical past? In ancient times information was passed down both in written and oral form. We see a hint of this in a passage found in Exodus 17:14.

Exodus 17:14: And the Lord said unto Moses, Write this for a memorial in a book, and rehearse it in the ears of Joshua: for I will utterly put out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven.

Here Moses is told to write in a book the message from God that God would wipe out the remembrance of the Amalekites. Moses is also told he is to verbally tell this to Joshua. Oral communication of information was common in the historical past. The ability to read was minimal and mostly limited to religious and governmental leaders. Moses was apparently educated at the courts of the Egyptian government and was able to read and write.

When Moses wrote what God commanded him to write, he wrote it using the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet, all of which are consonants. There are no vowels in the Hebrew alphabet. Neither would there have been punctuation. When Moses rehearsed what he wrote in the ears of Joshua, Moses supplied the vowels and punctuation in his speech to Joshua. Joshua could then take what he heard and pass it along to others. This is how much of communication was carried out in ancient times. The Hebrew Scriptures didn’t have vowels until early in the eight century A.D. In oral communication, the vowels are supplied by the speaker.

As covered earlier in this series, Around A.D. 700, a group of scholars called Masoretes worked to standardize the Hebrew Biblical text by comparing all known copies at the time and adding vowel points to standardize the pronunciation of the words. Prior to that time, the Hebrew Scriptures contained only consonants. The Codex Leningrad is the oldest surviving Masoretic text and was the oldest surviving Hebrew Bible prior to the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. All other manuscripts of the Hebrew Bible had been lost to antiquity except for a small papyrus fragment of 24 lines containing the Ten Commendments and the beginning of the Shema prayer. This fragment is known as the Nash Papyrus and is believed to date to 125 B.C. It was found in Egypt in 1848. With the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls, we now have copies of the Hebrew Scriptures that date back to somewhere between 250 B.C. and 50 A.D.

As also covered earlier in this series, the Torah (first five books of the Hebrew Scriptures) was translated into Greek around 250 B.C. The completed document became known as the Septuagint or LXX which is the Greek for the number 70. It is called the Septuagint because it is believed this translation of the Torah was completed in seventy days by a group of 72 Palestinian Jews. The rest of the Hebrew Scriptures were translated into Greek during the next 100 years and included the Apocrypha, a collection of writings not found in the canonized Hebrew Scriptures but are included in the Septuagint. A number of these Apocryphal writings are included in the Catholic Bible but have been rejected by most of the Protestant community. I say most because some English translations used by Protestants include the Apocrypha. The 1909 English Stand Version (ESV) includes the Apocrypha.

So while strictly speaking, the word Septuagint only refers to the translation of the Torah into Greek, the rest of the Hebrew Scriptures came to be translated into Greek and the entire translation came to be called the Septuagint as time passed. This included the Apocryphal writings. Apocryphal writings are writings that are not part of the canonized Scriptures but are, nevertheless, believed to be of value in contributing to our overall understanding of the canonized Scripture.

As previously mentioned in this series, all of the books of the Hebrew Scriptures are represented in the Dead Sea Scrolls except the book of Esther. Some scholars believe Esther is not found in the collection from Qumran because God is not mentioned in the canonized book of Esther. The lack of God being mentioned in the canonized book of Esther apparently was troubling to some scribes who over the centuries made copies of this book. Therefore, entire sections were added to the original book of Esther by scribes showing Esther and Mordecai, the two principle characters in this narrative, as offering up prayers to God. These additions were included in the Septuagint and eventually in the Latin translation of the Hebrew Scriptures called the Vulgate. These additions to Esther are present in the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Bible to this very day but are not found in most translations used by Protestants.

As discussed earlier in this series, the only complete book of the Hebrew Scriptures found at Qumran is Isaiah which is identified as 1QIsa(a). There were two Isaiah scrolls found at Qumran and both were found in cave one. 1QIsa(b) was about 75% complete whereas 1QIsa(a) is complete.

The partial Isaiah Scroll pretty much reflects what we see in the Masoretic texts from the early Middle Ages. Therefore, it is apparent that the Masoretes were using copies of the same Hebrew manuscripts used by the Qumran sect in writing what has been labeled 1QIsa(b). Remember it was the Masoretes who added vowel points to the Hebrew alphabet. The Masoretic Hebrew texts date from the early Middle Ages and are the texts commonly used to translate the OT from Hebrew into English and other languages. As already discussed, prior to the discoveries at Qumran, the Masoretic texts were the oldest known texts of the Hebrew Scriptures except for that small papyrus fragment from Egypt.

The complete Isaiah Scroll (1QIsa(a) ) is seen to have some differences in Hebrew wording when compared to the Hebrew manuscripts used by the Masoretes. Therefore, this Scroll was apparently made by copying from Hebrew manuscripts where scribes had inserted words they felt better reflected the thoughts of the original authors of Scripture. It is also possible that the Qumran scribes, themselves, made some changes in wording.

In the case of 1QIsa(b), which is the partial Isaiah Scroll found at Qumran, it matches very well with the Masoretic text of the tenth and eleventh centuries A.D. In the case of the complete Isaiah Scroll found at Qumran, there are some differences between it and the Masoretic text but these differences, often referred to as variants, are minor and have little impact on the meaning of the text.

Here is an example of just how minor the variants are. In the KJV, whose OT text is largely translated from the Masoretic manuscripts, is an ending to verse 24 of Isaiah chapter 3 that reads as follows:

Isaiah 3:24: And it shall come to pass, that instead of sweet smell there shall be stink; and instead of a girdle a rent; and instead of well set hair baldness; and instead of a stomacher a girding of sackcloth; and burning instead of beauty (KJV).

1QIsa(a) 3:24: And it shall be a stink there instead of spice and instead of a girdle a rope and instead of well set hair baldness and instead of a sash a girding of sack cloth, because instead of beauty shame.

In 1QIsa(a), this ending reads as “Instead of beauty shame.” A different Hebrew word is found in the Qumran text which means shame and is so translated in the English as seen in the above translation of this passage from the 1QIsa(a) Scroll. In the Masoretic text is a Hebrew word that means burning, branding or scaring. This word appears only this once in the Masoretic rendering of the Hebrew Scriptures and is translated “burning” in the KJV and “branding” in the NKJV and NIV.

And so it shall be: Instead of a sweet smell there will be a stench; instead of a sash, a rope; instead of well-set hair, baldness; instead of a rich robe, a girding of sackcloth; and branding instead of beauty (NKJV).

Instead of fragrance there will be a stench; instead of a sash, a rope; instead of well-dressed hair, baldness; instead of fine clothing, sackcloth; instead of beauty, branding (NIV).

The context of Isaiah 3 is the demise of Judah and the city of Jerusalem because of their failure to obey God. Verse 24 is part of a long list of miseries that are going to be suffered by Judah because of their sins. The Masoretic text has “burning instead of beauty.” The Qumran text has “Instead of beauty shame.” As can be clearly seen, the Qumran rendering in no way alters the overall meaning of what Isaiah is saying. Isaiah is saying that Judah is going to greatly suffer and whether he originally said “burning instead of beauty,” or “Instead of beauty shame.” The basic meaning is the same. Judah is going to lose its beauty and experience some very hard times.

The translators of the Revised Standard Version (RSV) of the Bible have used the Qumran 1QIsa(a) Scroll rendering of Isaiah 3:24 in producing their translation. Other translators of modern Biblical texts have not chosen to use the Qumran rendering of Isaiah 3:24.

Instead of perfume there will be rottenness; and instead of a girdle, a rope; and instead of well-set hair, baldness; and instead of a rich robe, a girding of sackcloth; instead of beauty, shame (RSV).

You will notice that every one of these renderings of Isaiah 3:24 translate the Hebrew words into English a little bit differently. In the case of the 1QIsa(a), we even find some Hebrew words used that are different from Hebrew words used in other manuscripts of this passage. This brings us to a discussion of translation.

TRANSLATION:

Translation is all about taking the meaning of a word or a phrase in one language and finding the best possible word or phrase to represent that meaning in another language. Translation is much more than word equivalency. It’s all about equivalency of meaning. There is another word that is used to designate strict word equivalency. It’s called transliteration. Transliteration is taking the alphabetic letters of a word in one language and matching them to the alphabetical letters of another language. For example, YHWH is an English transliteration of this Hebrew name for God. The four English letters YHWH are alphabetically equivalent to the Hebrew alphabetical letters that make up this word. We don’t know, however, how this transliterated Hebrew is actually pronounced as there aren’t any vowels. Most English versions of the OT Scriptures don’t use the transliteration YHWH but translate YHWH as LORD.

When translators work on rendering the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures into English or some other language, they strive to provide the best possible equivalency of meaning in translating from one language into another. They look at the oldest surviving Hebrew and Greek texts. They look at how words are used in other Hebrew and Greek literature that is still extant from the periods during which the Hebrew and Greek Scriptures were written. They look at how translators in the past have translated the Hebrew and Greek into English and other languages. After looking at all this, they still have to make a decision as to how to best render meaning contained in the words and phrases of one language into the words and phrases of another language. This is no easy task and mistakes are sometimes made. Translation invariably involves interpretation.

Some scholars believe many mistakes have been made and therefore we can’t know anything for sure as to what the original authors of Scriptural documents intended. Some scholars believe some translators and copyists have allowed their personal theological perspectives to influence their work and have therefore distorted what the original authors intended. Back in 1993, church historian and NT scholar Bart Ehrman wrote a book entitled “The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture” wherein he discusses the issue of translators and copyists of the NT Scriptures adding material to the NT narrative to promote their particular interpretation of what the Scriptural authors were saying. He provides a number of examples of such occurrences. A book published in October of 2011, and edited by renowned NT scholar Daniel Wallace, presents essays by a number of scholars who evaluate Ehrman’s work and further discuss the issues of copyist adding material to the manuscripts being copied. So the beat goes on relative to this issue.

Studies to date on the issue of Scriptural reliability have shown that there are inconsistencies, copyist mistakes, translation errors and both unintentional and intentional addition of material to Scriptural texts down through time. That being said however, it has also been shown through discoveries such as the Dead Sea Scrolls that, as a whole, the copying and translating of Scriptural material has not resulted in a corruption of the basic message and intent of Scriptural authors.

As I have discussed in other essays on this website, a document does not have to be totally inerrant to be reliable. In the past I have used the example of historical documents such as a history of the Civil War. You can read a dozen different authors who have written histories of the Civil War and each one will provide different perspectives as to various events associated with that war. However, they will all agree the war did take place, Abraham Lincoln was president of the Union and Jefferson Davis was president of the Confederacy, Generals Grant and Lee were notable military figures in the war and many other such details will be the same in all these histories. Therefore, there is no reason to disbelieve the basic accounts of what we call the Civil War.

So it is true with the Scriptures. The Hebrew and Greek Scriptures have been copied numerous times over the centuries and translated into most languages. Social, political, theological, cultural and educational dynamics have all played a role in the transmission of the Biblical Scripture. Yet despite all these dynamics affecting the transmission of the Biblical documents through time, it is noteworthy that the integrity of the texts has remained and there is remarkable consistency in their transmission regardless of what language these texts are translated into.

When we look at the four translations of Isaiah 3:24, we see four different renderings of various Hebrew words that make up this passage. Is one rendering more accurate than another? That’s not really the question to ask. The question to ask is whether all renderings reflect the general focus of what Isaiah is saying. By context we can see that they do. Isaiah is using figurative language to describe the misery that is going to be experienced by Judah because of their sins. Translating the Hebrew words Isaiah used into other languages will result in a variety of different words used to reflect the meaning of the Hebrew words Isaiah used. But, as can be seen, the meaning remains the same. Judah is going to experience great suffering because of its failure to follow God.

As I covered in the series dealing with the reliability of the Biblical Scriptures, you are going to find inconsistencies in the Scriptures. I provided several examples of inconsistencies in the reporting of the same event by different authors of the Gospel narratives. I also showed that despite inconsistencies between accounts of an event, the basic dynamics associated with such event were reported as being the same. For example, I discussed how Mark, Luke and John record Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey shortly before His arrest and crucifixion. Matthew has Jesus seemingly riding into Jerusalem on two donkeys. But, whether it was one or two, all four writers report Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey which was a sign of His kingship as this is the manner in which victorious kings of Israel rode into Jerusalem. This is the primary focus in reporting this event.

When reading Biblical Scripture, in is important to consider overall context of what is being said or reported. Audience relevance is also an important dynamic in determining what is being said. Audience relevance has to do with coordinating what is being said with the cultural, social, political and religious dynamics extant at the time the words were said or written and not with such dynamics extant in one's own time. In other words, when studying the Scriptures, we must always ask what a prophecy from Isaiah, a Gospel from Matthew or a letter from Paul, means to the original recipients of what they said and wrote

In studying the Dead Sea Scrolls, we find the same interpretative dynamics extant that are found in the writings of religious groups throughout history. Most religious groups throughout history have tended to interpret their historical writings in light of their present perspectives and current circumstances. That practice continues to this very day. Just look at all the different contemporary perspectives and applications of Bible prophecy. The Qumran group was no different. We saw how they interpreted the book of Habakkuk to apply to their own day. Much of their writing reflects this same approach.

The main thing the Scrolls do for us is to provide confidence that there has been little change in the text of the Hebrews Scriptures over the centuries of transmission. Scribes have been very faithful in accurately copying these texts. While there are variants, additions and subtractions evident in the transmission of these texts, the overall integrity of the transmitted texts has been maintained. This is the primary lesson we can learn from the discoveries at Qumran.

So what is the overall lesson we learn from having manuscripts of Isaiah and other OT documents that date back to several hundred years before Christ? We learn that our English and other foreign language translations of these Hebrew documents are consistent with copies of this text that go back over two thousand years. There is little variation in text between the Qumran copies of Isaiah and the Masoretic Hebrew texts from the tenth and eleventh centuries A.D. This was also found to be true when comparing the various Qumran fragments of other books of the Hebrew Scriptures with the Masoretic Hebrew texts.

In other words, in the thousand or so years between the Qumran documents and the Masoretic texts of the early Middle Ages, there is little variation in the text. We don’t know how old were the copies of the Hebrew texts of the OT used by the Masoretes. All such documents have been lost to antiquity. But it is apparent from comparing the Qumran texts with the Masoretic texts there is great consistency in what is written. Its apparent copyists have carefully transmitted the Hebrew Scriptures from one generation to another with only minor variation found in the text. Therefore, we can have confidence that the Hebrew Scriptures have been faithfully transmitted through time and this is the main lesson we can take away from our study of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

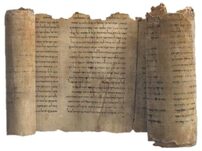

The Dead Sea Scrolls are permanently housed in the Shrine Of The Book located in West Jerusalem as seen on the left. From time to time a selection of the scrolls are transported to libraries and other venues around the world for viewing. Because of their fragile condition, they are kept in sealed, temperature controlled containers. I had the privilege of viewing many of the scrolls when I was in Jerusalem in 1994 and I highly recommend viewing them if they should ever come to your area

The Dead Sea Scrolls are permanently housed in the Shrine Of The Book located in West Jerusalem as seen on the left. From time to time a selection of the scrolls are transported to libraries and other venues around the world for viewing. Because of their fragile condition, they are kept in sealed, temperature controlled containers. I had the privilege of viewing many of the scrolls when I was in Jerusalem in 1994 and I highly recommend viewing them if they should ever come to your area